Electro-codeposition of MCrAlY Coatings for Advanced Gas Turbine Applications - 8th Quarterly Research Report

This NASF-AESF Foundation research project report covers the eighth quarter of project work (October-December 2019) on AESF Foundation Research at Tennessee Tech. The objective of the work is to study and optimize the MCrAlY electro-codeposition process to improve the coating oxidation/corrosion performance. In this quarter, the effects of particle density and shape on codeposition were studied. The results show that the shape of the particles plays an important role.

#research #nasf

Editor’s Note: This NASF-AESF Foundation research project report covers the eighth quarter of project work (October-December 2019) on an AESF Foundation Research project at the Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville, Tennessee. A printable PDF version of this report is available by clicking HERE.

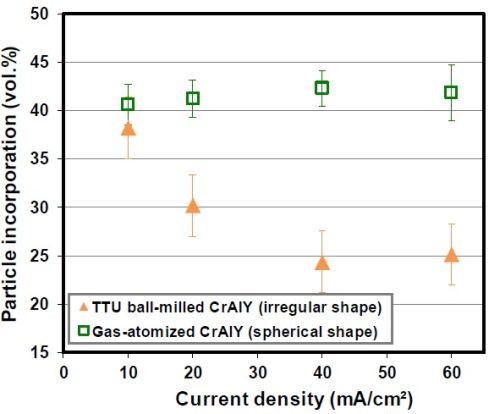

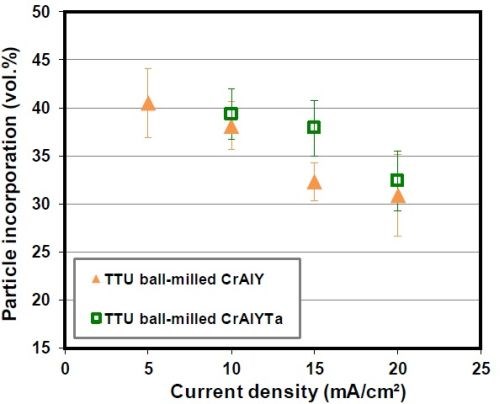

Summary: In the fourth quarter of Year 2, the effects of particle density and shape on the codeposition process were studied. Both gas-atomized and ball-milled CrAlY powders were used in electro-codeposition, which displayed spherical and irregular shapes, respectively. The particle size range of ball-milled CrAlY powder was sorted and selected using water elutriation so that the two types of powders exhibited similar particle sizes (D50 = 10-11 μm). Under the same codeposition conditions, the CrAlY particle incorporation was ≤ 30 vol% when the irregularly-shaped powder was used, while greater than 40 vol% particle incorporation was obtained for the spherical gas-atomized powder. The gas-atomized CrAlY powder had a slightly higher density (5.0 g/cm3) than the ball-milled powder (4.5 g/cm3). In order to confirm that the increase in particle incorporation was mainly due to particle shape rather than particle density, ball-milled CrAlY and CrAlYTa powders with different densities were employed in the electro-codeposition process. Only very small increases of particle incorporation were observed for the CrAlYTa particles with a higher density. The results suggest that the shape of the particles plays an important role in electro-codeposition, likely related to the specific surface area of the particles which can affect the number of metal ions adsorbed on a particle surface.

Featured Content

Technical report

I. Introduction

To improve high-temperature oxidation and corrosion resistance of critical superalloy components in gas turbine engines, metallic coatings such as diffusion aluminides or MCrAlY overlays (where M = Ni, Co or Ni+Co) have been employed, which form a protective oxide scale during service.1 The state-of-the-art techniques for depositing MCrAlY coatings include electron beam-physical vapor deposition (EB-PVD) and thermal spray processes.1 Despite the flexibility they permit, these techniques remain line-of-sight which can be a real drawback for depositing coatings on complex-shaped components. Further, high costs are involved with of the EB-PVD process.2 Several alternative methods of making MCrAlY coatings have been reported in the literature, among which electro-codeposition appears to be a more promising coating process.

Electrolytic codeposition (also called “composite electroplating”) is a process in which fine powders dispersed in an electroplating solution are codeposited with the metal onto the cathode (specimen) to form a multiphase composite coating.3,4 The process for fabrication of MCrAlY coatings involves two steps. In the first step, pre-alloyed particles containing elements such as chromium, aluminum and yttrium are codeposited with the metal matrix of nickel, cobalt or (Ni,Co) to form a (Ni,Co)-CrAlY composite coating. In the second step, a diffusion heat treatment is applied to convert the composite coating to the desired MCrAlY coating microstructure with multiple phases of β-NiAl, γ-Ni, etc.5

Compared to conventional electroplating, electro-codeposition is a more complicated process because of the particle involvement in metal deposition. It is generally believed that five consecutive steps are engaged:3,4 (i) formation of charged particles due to ions and surfactants adsorbed on particle surface, (ii) physical transport of particles through a convection layer, (iii) diffusion through a hydrodynamic boundary layer, (iv) migration through an electrical double layer and (v) adsorption at the cathode where the particles are entrapped within the metal deposit. The quality of the electro-codeposited coatings depends upon many interrelated parameters, including the type of electrolyte, current density, pH, concentration of particles in the plating solution (particle loading), particle characteristics (composition, surface charge, shape, size), hydrodynamics inside the electroplating cell, cathode (specimen) position and post-deposition heat treatment, if necessary.3-6

There are several factors that can significantly affect the oxidation and corrosion performance of the electrodeposited MCrAlY coatings, including: (i) the volume percentage of the CrAlY powder in the as-deposited composite coating, (ii) the CrAlY particle size/distribution and (iii) the sulfur level introduced into the coating from the electroplating solution. This three-year project aims to optimize the electro-codeposition process for improved oxidation/corrosion performance of the MCrAlY coatings. The three main tasks are as follows:

- Task 1 (Year 1): Effects of current density and particle loading on CrAlY particle incorporation.

- Task 2 (Year 2): Effect of CrAlY particle size on CrAlY particle incorporation.

- Task 3 (Year 3): Effect of electroplating solution on the coating sulfur level.

In the previous reporting period (Seventh Quarterly Report: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF19Dec2), the effect of the particle size of both ball-milled and gas-atomized powders CrAlY powders on the particle incorporation in the (Ni,Co)-CrAlY composite coatings was studied. In the current study, the influence of CrAlY(Ta) particle density and shape on the particle incorporation was investigated.

II. Experimental procedure

Disc specimens of Ni-based alloys (1.6 mm thick, ~17 mm in diameter) were ground to #600 grit using SiC grinding papers, followed by grit blasting with #220 Al2O3 grit. The specimens were then ultrasonically cleaned in hot water and acetone prior to electro-codeposition. Pre-alloyed CrAlY(Ta) powders with different densities and shapes were utilized. The spherical CrAlY powders were manufactured by gas atomization and were purchased from Sandvik. The CrAlY(Ta) powders with irregular shapes were made via arc melting and ball milling at Tennessee Technological University (TTU). Both powders were sieved through a 20-μm screen (625 mesh). Water elutriation was employed to select the particle size range of some ball-milled CrAlY powder to make it more comparable to the size of the gas-atomized powder.7

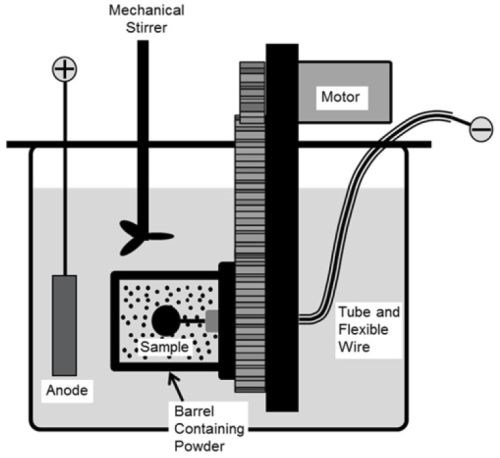

A rotating barrel system as illustrated in Fig. 1 was used in the electro-codeposition experiments; details can be found elsewhere.6 Watts nickel plating solution was utilized in electro-codeposition. The solution pH was kept at ~3.5 and the solution temperature was at 50 ± 1.5°C. The CrAlY(Ta) particle concentration in the solution was 20 g/L, while the applied current density ranged from 5 to 60 mA/cm2. The specimens were plated for different lengths of time, depending on the required coating thickness and the applied current density.

Figure 1 - Schematic of the barrel system.

Particle size analysis was carried out using a Malvern Mastersizer 2000 Laser diffractor. The density of the alloy powder was determined using a pycnometer (Micromeritics AccuPyc II 1340 Pycnometer). The NiCo-CrAlY(Ta) composite coatings were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) equipped with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). Prior to metallographic sample preparation, the specimens were copper-plated to improve edge retention. To determine the volume fraction of the incorporated CrAlY(Ta) particles, multiple backscattered electron images were taken from different locations along the coating cross-section, which were then processed using the ImageJ software.8 The brightness and contrast of the image were adjusted by setting a proper threshold to separate the particles from the background. The area fraction of the CrAlY(Ta) particles was determined, which was assumed equivalent to its volume fraction.

III. Results and discussion

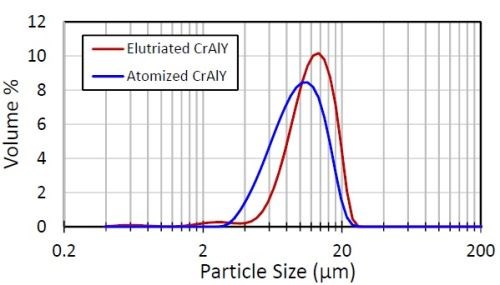

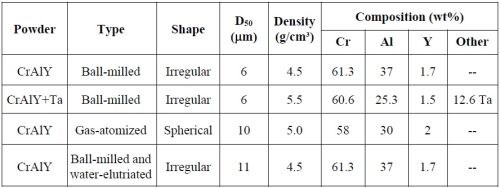

The particle size distributions of the gas-atomized (spherical) and ball-milled (irregular) CrAlY powders are presented in Fig. 2 and summarized in Table 1. After water elutriation, the ball-milled powder exhibited a particle size very similar to that of the gas-atomized powder. This also further confirms that water elutriation is an effective method in sorting out and selecting the particles with desired particle size range. D50 values of the spherical and irregular particles were 10 mm and 11 mm, respectively. The spherical particles had a slightly higher density (5.0 g/cm3) than the irregular particles (4.5 g/cm3).

Figure 2 - Particle size distributions of gas-atomized (spherical) CrAlY powder and ball-milled (irregular) powder after water elutriation.

Table 1 - Particle properties of CrAlY-based powders used in electro-codeposition.

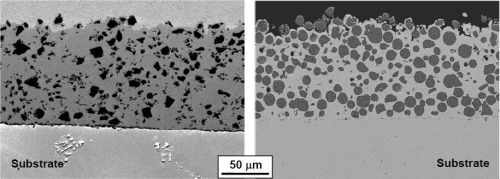

Figure 3 shows the SEM cross-sectional images of the Ni-CrAlY coatings that were deposited using the two types of powders. The differences in the CrAlY particle shape can be clearly seen. The CrAlY particle incorporation as a function of current density is presented in Fig. 4. Under the same codeposition conditions, the CrAlY particle incorporation was £ 30 vol% when the irregularly-shaped powder was used, while greater than 42 vol% of particle incorporation was obtained for the spherical gas-atomized powder.

(a) (b)

Figure 3 - Cross sections of Ni-CrAlY coatings deposited using (a) ball-milled and (b) gas-atomized powders.

Figure 4 - Effect of the CrAlY particle shape on particle incorporation.

The gas-atomized CrAlY powder had a slightly higher density (5.0 g/cm3) than the ball-milled powder (4.5 g/cm3). In order to confirm that the increase in particle incorporation was mainly due to the particle shape rather than the density, ball-milled CrAlY and CrAlYTa powders with different densities were employed in the electro-codeposition. As shown in Fig. 5, only very small increases of particle incorporation were observed for the CrAlYTa particles with a higher density. Hence, most of the changes in particle incorporation were due to the difference in particle shape between the spherical gas-atomized powder and the irregular ball-milled powder.

Figure 5 - Effect of CrAlY(Ta) particle density on particle incorporation.

So far, most studies related to the effects of particles has been focused on chemical composition, size and conductivity of the particles.9-12 In contrast, the effects of particle size shape and density have not received much attention. The results of the present study suggest that the shape of the particles plays an important role in the electro-codeposition process. These results are also consistent with the findings by Apachitei 13 where the spherical Al2O3 particles were found to lead to an increase in particle incorporation compared to the irregular Al2O3 particles in the NiP-Al2O3 coatings (i.e., 33 vs. 28 vol%). The author attributed the increase in particle incorporation to decreases in the specific surface area of the particles. A possible theory is that spherical particles with lower specific surface areas require fewer metal ions to be deposited for a given volume, resulting in an increase of the volume of particles relative to the volume of deposited metal.

References

- G.W. Goward, Surf. Coat. Technol., 108-109, 73-79 (1998).

- A. Feuerstein, et al., J. Therm. Spray Technol., 17 (2), 199-213 (2008).

- C.T.J. Low, R.G.A. Wills and F.C. Walsh, Surf. Coat. Technol., 201 (1-2), 371-383 (2006).

- F.C. Walsh and C. Ponce de Leon, Trans. Inst. Metal Fin., 92 (2), 83-98 (2014).

- Y. Zhang, JOM, 67 (11), 2599-2607 (2015).

- B.L. Bates, J.C. Witman and Y. Zhang, Mater. Manuf. Process, 31 (9), 1232-1237 (2016).

- L.R. Follmer and A.H. Beavers, J. Sedimentary Res. (formerly J. Sedimentary Petrology), 43 (2), 544-549 (1973).

- C.A. Schneider, W.S. Rasband and K.W. Eliceiri, Nat. Methods, 9 (7), 671–675 (2012).

- D.F. Susan, K. Barmak and A.R. Marder, Thin Solid Films, 307 (1-2), 133-140 (1997).

- R. Bazzard and P.J. Boden, Trans. IMF, 50 (1), 63-69 (1972).

- J. Foster and B. Cameron, Trans. IMF, 54 (1), 178-183 (1976).

- L. Stappers and J. Fransaer, J. Electrochem. Soc., 153 (7), C472-C482 (2006).

- I. Apachitei, Synthesis and characterisation of autocatalytic nickel composite coatings on aluminium, PhD Dissertation, Delft University of Technology (The Netherlands), 2001.

Past project reports

1. Quarter 1 (January-March 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 82 (12), 13 (September 2018); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF18Sep1.

2. Quarter 2 (April-June 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (1), 13 (October 2018); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF18Oct1.

3. Quarter 3 (July-September 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (3), 15 (December 2018); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF18Dec1.

4. Quarter 4 (October-December 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (7), 11 (April 2019); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF19Apr1.

5. Quarter 5 (January-March): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (10), 11 (July 2019); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF19Jul1.

6. Quarter 6 (April-June): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 84 (1), 17 (October 2019); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF19Oct2.

7. Quarter 7 (July-September): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 84 (3), 16 (December 2019); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF19Dec1.

About the authors

Dr. Ying Zhang is Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Tennessee Technological University, in Cookeville, Tennessee. She holds a B.S. in Physical Metallurgy from Yanshan University (China)(1990), an M.S. in Materials Science and Engineering from Shanghai University (China)(1993) and a Ph.D. in Materials Science and Engineering from the University of Tennessee (Knoxville)(1998). Her research interests are related to high-temperature protective coatings for gas turbine engine applications; materials synthesis via chemical vapor deposition, pack cementation and electrodeposition, and high-temperature oxidation and corrosion. She is the author of numerous papers in materials science and has mentored several Graduate and Post-Graduate scholars.

Dr. Jason C. Whitman is a Materials Lab Engineer at National Aerospace Solutions, LLC at Arnold AFB, Tennessee. His primary work with AESF Foundation Research Project R-119, was as a Graduate Research Assistant at Tennessee Technological University in Cookeville, Tennessee, from which he earned a B.S. degree in Mechanical Engineering (2012), and a Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering in (2018).

*Corresponding author:

Dr. Ying Zhang, Professor

Department of Mechanical Engineering

Tennessee Technological University

Cookeville, TN 38505-0001

Tel: (931) 372-3265

Fax: (931) 372-6340

Email: yzhang@tntech.edu

RELATED CONTENT

-

Aluminum Anodizing

Types of anodizing, processes, equipment selection and tank construction.

-

A Chromium Plating Overview

An overview of decorative and hard chromium electroplating processes.

-

Nickel Electroplating

Applications, plating solutions, brighteners, good operating practices and troubleshooting.